This page is dedicated to the Synagogue of Dura-Europos, close to the modern Deir-Ez-Zur in Syria. It is a digital project for the course, The Art and Archaeology of the Graeco-Roman Near East and Egypt, taught by Professor Elisabeth Macaulay-Lewis in the spring of 2013 at the CUNY Graduate Center, New York.

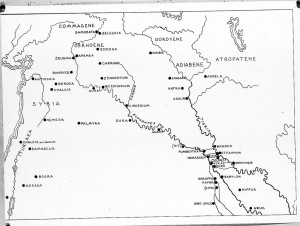

Dura-Europos is located on the west bank of the middle Euphrates River, close to the modern location of Qualat al Salihiya in Syria. It is about 100 km southeast of Deir-Ez-Zur. The archaeological site is situated on a high, flat plateau between two ravines in the north and south. While there is the desert on the west side of the town, the high bank of the river offered natural protection in the east. In the town itself, there were also wadis. In contrast to the fertile areas of the Euphrates Valley, Dura-Europos was situated in a desert region. The distance between Dura-Europos and Palmyra, the major city in the area, is 267 km. The distance from Babylon is 270 km.

“Pompey of the East”

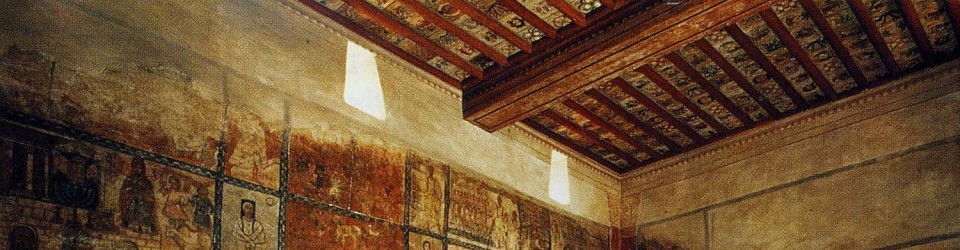

Clark Hopkins, an archaeologist from the joint expedition of the Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, was greatly surprise when in the fall of 1932 he saw for the first time the painting of the synagogue after the dirt had been cleared: “It was a scene like a dream! In the infinite space of clear blue sky and bare gray desert, there was a miracle taking place, an oasis of painting springing up from the dull earth.”1 And in fact this discovery greatly changed many scholarly assumptions about the location of ancient synagogues, their interior furnishings and the use of iconographic material in sacred space, thus meriting the title “Pompey of the East.” Nearly a century later, after an abundance of studies, it is possible to better understand not only ancient synagogues in general, but also Jewish life in a city populated by many different ethnicities at a “crossroads” of the ancient world: the border of the Roman Empire in the first centuries of the Common Era.

For over 1,700 years, the site was hidden by sand and embankments in the dry climate of the area, preserving it exceptionally well to enable posterity to study the history of Dura-Europos in depth. This is the all-the-more important as scant literary sources are available about the area. The paintings were cut out by the architect Henry Pearson and reconstructed together with the synagogue’s court in the National Museum of Damascus in Syria as the Museum itself was being built. They constitute its eastern wing. A firsthand report of Annabel Wharton: “In the spring of 1992, I was given permission to photograph anything in the Museum, except the synagogue frescos[…] Though accessible upon request, the presence of the synagogue frescoes in the museum is nowhere announced. Even in some foreign guidebooks, the synagogue itself is censored in the plans of the museum’s galleries.”2

It is thus understandable that the paintings were not easily accessible and that many scholars had to rely on old photographs and other later reproductions. Many assessments, in fact, have been made by scholars without ever having seen the artifacts in person, with all the limits that this implies. The recent civil war in Syria is causing not only a terrible massacre of innocent people but the destruction of precious archaeological sites, endangering forever the possibility to see a large part of the remains of Dura-Europos. The fate of the paintings is also unclear.

Beautiful painted tiles decorated the synagogue’s ceiling. They can be viewed at the Yale University Art Gallery. Herbert Gute’s copies of the paintings are also in the Gallery. They are very precious since Gute copied them at the excavation site shortly after they were discovered. The colors and all the details were clearly visible at the time, and had not yet faded through exposure to light. A few tiles are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Jewish Museum New York and the Louvre in Paris.

- Clark Hopkins, “The excavations of the Dura Synagogue Paintings,” in The Dura-Europos Synagogue: A Re-evaluation (1932–1992), ed. J. Gutmann (Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1992), 16. ↩

- Wharton 1995, 42. ↩

Thank you for posting this. This year’s curriculum of the Jewish Culture School of the Tri-Valley Cultural Jews is “Jewish HIstory Through Art” and I’ve used information on this site.