A considerable quantity of graffiti from the synagogue is preserved, offering further insights into the world of the Jews in Dura-Europos. The custom to write and draw on paintings or on walls or wherever the person desired, with no concern about ruining or damaging the environment, was common in the ancient world (and probably also survives in the modern world). Caution is required, since the ephemeral character of this writing, whose letters are not engraved or painted but scratched, makes it difficult to read.

There are no extant originals or photos of the graffiti of the earlier synagogue. Graffiti nos. 18, 19, 20-22 Torrey in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 81, 82, 83 are remarkable since they are the only ones left from the early synagogue building. The readings are based on the drawings of the originals made by Du Mesnil du Buisson soon after the graffiti were discovered. The early building’s inscriptions, Syr 81 and 82, were preserved since they were located in the core of the synagogue’s western wall. Made up of few letters, the corrupted text has been deciphered in so many different ways, leaving room for much conjecture, and, for this reason, will not be discussed here.

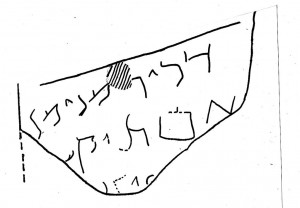

Syr 83 was written in Aramaic on a plaster fragment of a doorjamb but the findspot is not clear, probably Room 7 of the earlier building or, according to another report of Rostovtzeff, in the peristyle court, a confusion deriving perhaps, from the fact that the two places were adjacent. 1 Kraeling supposes that the plaster was part of the trim of the south door.2

Inscription no.20-22 Torrey in Kraeling 1956=Syr 83

Translation of Noy-Bloedhorn (IJO 2004, 138):

(a) This is the inscription which Matthenai wrote.

(b) By your leave; Hanani and Dakka and Nahmani, may he be remembered

(c) May Minyanim be remembered, the apothecarius(?).

The letter “h” in Hanani and Nahmani is uncertain.

Torrey considers these graffiti three separate inscriptions. Another interpretation is that (a) Matthenai is the painter himself, (b) and (c) names of the donors. The text scratched on the door jamb draws the attention of the readers when leaving, praying to be remembered. The meaning of “apothecarius” is unclear. He could have been someone in charge of a magazine or an army commissary.3 The meaning of the author’s text lies in his request to be remembered.

Similarly to the earlier building there are no originals or photos available of the graffiti from the later building.4

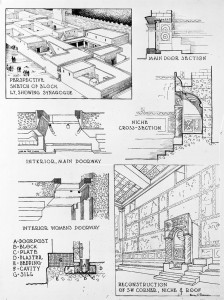

Some graffiti have been re-evaluated by Stern.5 The author made a comparative study of names and remembrance graffiti. In particular, she claims that graffiti are “clustered” on doorjambs and on a single lintel in the synagogue and identifies this as a testimony of a specific devotional practice.

The graffiti in question are, according to the classification in IJO: Syr 83, 93, 94, in Aramaic and one in Middle Persian, Syr 126, and are very damaged. On a lintel is only the graffito Syr 92. Although common sense suggests that areas around doors are more frequented and perfect for a graffiti-writer in search of an audience, the author claims that other cultic reasons brought the attendees of the synagogue to choose precisely the doorjambs from among all places. The reason for this preference was the mystic-religious function attributed to the door. According to an old excavation report, in fact, the early excavators found bones, parts of two human fingers, in a socket under the sill of the door. This discovery was interpreted as a “foundation deposit,” a practice common to pagan temples and widespread in the ancient world. Under these circumstances, the door would represent a sacred space and tagging doorways would be an act of prayer or personal advocacy.6

A few brief observations to gain a broader overview of this issue:

First, the deposit of bones mentioned in Excavation Report VI, p. 316 does not exist anymore and could not be verified even in the past since it disappeared during the last war. Kraeling prudently writes that the report was not verified and the alleged presence of a foundation deposit needs to be connected to the “evidence of additional liberties exercised by the Jews in Dura” by which he means the paintings in the synagogue.7 Furthermore, human fingers as a bone deposit are a rare occurrence. Animal bones have sometimes been found, since sacrifices were occasionally made in the area.

The author’s statement (Stern, 2012, 189, n.71) that the Talmud (Berakhoth, 18b) describes doorposts as a place to hide possessions is not substantiated and represents a misinterpretation of Berakhot, 18b. The only passage discussing possessions hidden under a door is a tale, similar to a fabula, relating generally to the relations between the living and the dead, which mentions a woman who hid the money of her tenant under the door before she died. The tenant had to go to the cemetery to ask the dead woman where his money was and in this way he found it. Thus, there is no suggestion in Berakhot , 18b that anyone should hide valuables under doors.

Finally, the use of the mezuzah on doorposts does not mark the door as a sacred space, but instead affords a moment to remember God’s commandments when going in and out of a place. Thus, while it is surely correct to recognize the importance of the graffiti on doorjambs for purposes of remembrance and as an expression of religious devotion, with or without the presence of the bones, this statement should not be overemphasized due to the scant quantity of graffiti and the absence of originals.8

- IJO 2004, 138 ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 274. ↩

- IJO 2004, 139. ↩

- Syr 90 = No. 35 Welles in Kraeling 1956. Syr 93 = Nos. 12-14 Torrey in Kraeling. Syr 94 =Nos. 15-16 Torrey in Kraeling. Syr 95 = No. 17 Torrey in Kraeling. Syr 91 and Syr 92 are not in the excavation report of Kraeling. ↩

- K. B. Stern, “Tagging Sacred Spaces in the Dura-Europos Synagogue,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 25, (2012): 188-89. ↩

- Stern 2012, 191. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 19 n. 86. ↩

- An example of a bad source is the inscription Syr 92 on a lintel, not accepted in Kraeling. This graffito was published without any details by Du Mesnil du Buisson. It is remarkable that it would be the only graffito on the lintel preserved with both Aramaic and Greek in the same text. It was found in a spot 50 meters from the synagogue and was probably from another building since the synagogue did not have lintels in situ. The dating is very controversial since Du Mesnil du Buisson did not explain where the alleged date came from. See: IJO 2004, 157. ↩