This section is dedicated to an analysis of iconographic elements in the paintings in order to identify Graeco-Roman influences and to understand the relation between the Jews and their enviroment in Dura-Europos. In the Ezekiel panel, hands have the iconographic function of explaining the narrative. The motif of The Hand of God appears five times in the panel, a motif, which at most contravenes the biblical prohibition against drawing images. On the basis of current knowledge, The Hand of God is very uncommon in Jewish synagogues and is only present in the floor mosaic of the fifth-century Beth Alpha synagogue in Israel. However, the little Hand of God coming out from a cloud in Beth Alpha’s mosaic is not comparable to the hands in Dura’s paintings.

In the art of the Near East, the Hand of God was established since ancient time as sign of blessing or protection. Some examples are also to be found in Palmyra and in pagan art in Dura (Hachlili 1998, 145).

All in all, the hands in the Ezekiel panel have the remarkable function of directing the narrative and are dynamic in contrast to the rigidity of the body of the men. The narrative’s language is better articulated through the hands. Furthermore, the hands of Ezekiel are in “dialogue” with the Hands of God. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the motif of the Hand of God also appears in WA 3: “Exodus and Crossing of the Red Sea.”

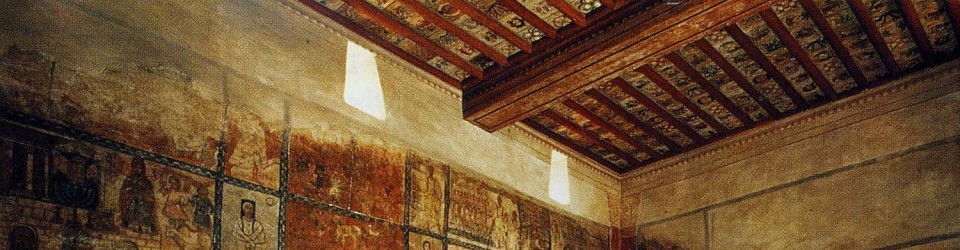

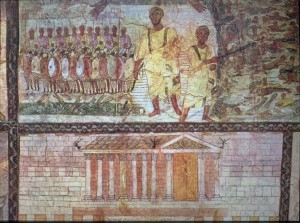

Upper panel: “The Children of Israel Crossing the Red Sea”. Below: Temple (Art Images for College Teaching)

Here in the story of the parting of the sea a first Hand of God points to the “Drowning of the Egyptians” in the sea while Moses standing on the side extends the staff over the water, realizing the miracle. In the second scene Moses is standing while the Jews and the twelve elders (representing the twelve tribes) are crossing the Red Sea; from above the second Hand reaches towards the Jews, indicating here too the realization of a wonder. The two Hands, a left and a right one, are reaching down giving the impression of a wide embracing gesture. This iconographic expression seems to be literally connected with Deuteronomy 26:8 where is mentioned: “Hashem brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and with an outstretched arm.”

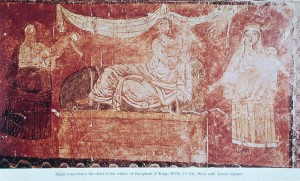

Similarly in WC 1, “Elijah Revives the Widow Child,” a hand from above reaches down in the direction of the revived child held by the prophet Eljiah.

In the painting, “Moses and the Burning Bush,” on Wing Panel 1 on the right side of the Torah shrine, the Hand points to the bush, although the fire is clearly a sign of the presence of God. On the upper edge of the painting over the Torah shrine, “The Sacrifice of Isaac,” a little Hand of God crops up from a cloud, very similar in style to the type in Beth Alpha. This picture was probably also part of the early decoration of the synagogue. (See the painting above).

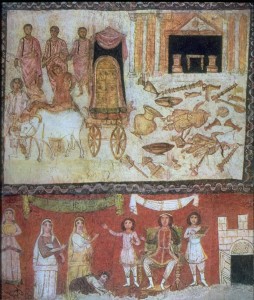

In general the relation between the Jews and their God, as expressed in the scenes of the paintings, could have a strong impact on the viewers as could, for example, the images of the destroyed pagan statues in the episode of the “The Ark in the Land of the Philistines” in WB 4. This panel refers to the story of the Battle of Eben-Ezer between the Philistines and the Jews as told in the Book of Samuel, 5-6. After the defeat of the Jews, the Philistines captured the ark which was brought into the temple of Dagon in Ashdod and put beside the image of the god. In the two ensuing days, the ark caused the fall of Dagon’s statue, which was damaged. After causing further destruction in several towns where it was sent, the ark was attached to a cart drawn by two milch-kine and allowed to go wherever it was brought by them.

The identification of the destroyed statues laying damaged on the floor in the temple of Dagon was highly debated. It suffices here to say that they wear a Persian costume similar to the tailored suite, i.e. tunic and pants and soft boots and a chlamys over the shoulder. The artist doubled the figures according Samuel’s story, because there Dagon’s statue fell down for two consecutive days. The objects on the floor would be tropaia, according to the convention in imperial Roman art, to display a victory, in this case the victory of the Jews over the Philistines. The panel “The Ark in the Land of the Philistines” in fact, counterbalances the defeat represented in the panels of “The Battle of Eben-Ezer” (NB 1). There are no decisive elements to identify the two statues as Adonis according to Du Mesnil du Buisson’s suggestion, and the most probable theory is that the local artist portrayed a deity in a fashion familiar to him, having no idea of a Dagon.1 A reading based on the details of the painting, which moreover does not disconnect the Dagon panel (WB 4) from its own contextual narrative scenes (1 and 2 as in Panel NB 1) undermine a supposed “antagonistic” interpretation. The context of the biblical narrative expresses the recurrent motif of the powerful God, in this case able to punish the Jews through defeat and to forgive them with the wonders of “the Ark.”

Above: “The Ark in the Land of the Philistines”. Below: “Pharaoh and the Infancy of Moses” (Art Images for College Teaching)

Nonetheless, some scholars have taken into account the possibility of non-Jewish visitors as recipients/addressees of a supposed antagonistic meaning of “The Ark” and of scenes in the Elijah cycle. In the latter, Baal’s priests are put to shame for a failed miracle.2

Moreover, according to Rajak3 non-Jews, above all Christians, might have been attracted to the synagogue by the many scenes of resurrection.

Surely the general meaning of the paintings could have been intuitively understood by non-Jews or by non-educated Jews. The depiction of the Temple and Aaron, for example, or Elijah’s stories provide tools for understanding the narrative through their sequences, repetition of figures, gestures and dresses. Nonetheless, on parts of the western wall, short painted inscriptions, “tituli,” written on the paintings mostly in Aramaic, identified the figures. It is not clear if they were discontinued because they were considered useless or for other reasons.

Here a brief selection: Exodus’ panel, WA 3: “Moses, when he went forth from Egypt and parted the sea,” (translation by Noy-Bloedhorn, Syr 96). Panel of Samuel, WC 3: “Samuel when he anointed David. Behold (?)or [Hannah].” The inscription is not completely clear. (Translation by Noy-Bloedhorn, Syr 103.) Panels of Elijah, WC 1:”Elijah”(Syr 105). Purim panel, WC 2, “Mordecai,” “Ahasuerus” and “Esther,” ( Syr 104).

Only the name of “Aaron” appears in Greek as a titulus in the panel WB 2, “The Consecration of the Tabernacle and its Priests” (Syr 102). In the Ezekiel paintings, the story of the resurrection of the dead and the representation of the Hand of God does not have tituli. If educated Jews did not require any further “aid” to understand the paintings, for whom were the inscriptions meant? Were the stories of Purim or of the prophet Elijah not popular and well known? Considering that the language of the tituli on the paintings is Aramaic, with only one being in Greek, mostly the Aramaic speaking population should have benefitted of them. The Jews in Babylonia, Syria and Palestine mainly spoke Aramaic, and these explanations were probably for those not well versed in the Biblical texts.

However, the obviousness of some tituli, such as Aron, Esther or “Moses parting the sea,” might suggest that non-Jews visited the synagogue as well.

In conclusion, the paintings were not directed primarily to non-Jewish visitors, nor were they used as part of a political or religious “campaign” for or against other cults or populations.4 It would be a mistake to impose modern perspectives on the ancient world. The question about the reactions of non-Jewish visitors elicits a predictable negative answer and presupposes a conflictive attitude on the part of the patrons and worshippers of the synagogue. As a matter of fact, the paintings, “The Ark in the Land of Philistines” and the Elijah cycle, provide the only clear statement against idolatry among all the remaining paintings, which display a great variety of Graeco-Roman and oriental influences. This implies a Jewish environment more appreciative of the pagan world, than concerned with the stringencies of Jewish Law.

An evident Graeco-Roman influence is the acceptance of naked figures in the paintings. The daughter of Pharaoh in the panel, “Infancy of Moses” (WC 4), is naked as is Aphrodite (Hachlili 1998, 192) and dominates the lower more visible Section C of the western wall, the same which hosts the Torah shrine. Naked bodies of Egyptians drowning in the sea are also to be found in the Exodus panel depicting the crossing of the Red Sea (WA 3).

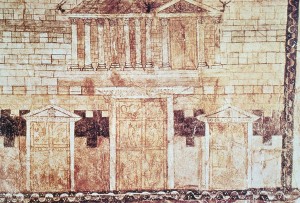

But it is somehow unexpected to see naked male figures similar to Hellenistic gods and Tyche, a female figure wearing bodice and skirt, on the door of the building interpreted as the Temple of Jerusalem (WB 3), which is represented as “an excellent Hellenistic temple” (Kraeling 1956, 109), although this identification is disputed.5

In the Ezekiel panel, naked dead bodies lay on the ground and the widow of Zarephath has, for unknown reasons, bare feet and a bare upper part of the body.6 There can be no doubt that the representation of conventional naked figures within the sacred space was not a concern for the worshippers in the synagogue of Dura-Europos. The mixture of Hellenistic elements and Jewish motifs seems widespread and marks a difference between the decorations of the earlier synagogue and the later building. While Jewish identity was undeniably expressed through the representation of biblical and rabbinical texts, on the other hand elements of Greek and Roman culture are adapted without apparently causing difficulties for the worshippers. Thus, in the same synagogue, the panel (WB 4), “The Ark in the Land of the Philistine,” shows pagan idols destroyed on the floor by the invisible power of the Jewish Ark, while winged figures like Victorias are on the roof of the Temple of Jerusalem and pagan figures are depicted on its door (WB 3).

The mantel of the priest Aaron (WB 2) was not drawn as minutely described in the Pentateuch but is very similar to the coat of a Hatra king as depicted in a later Sassanian relief in Taq-e Bustan (Hachlili 1998, 138). This would speak not in favor of a polarity of opposition/assimilation to the non-Jewish environment, but in favor of a Jewish composite group, probably Greek, Babylonian and Syrian, willing to adopt the artistic expressions of Greco-Roman culture in the synagogue and to merge the different Jewish geographical origins within the group self. This tolerant attitude regarding art does not exclude pious practices.

Sassanian relief of Taq-e Bustan representing the crowning of King Chosraus II (sixth c. CE). The god on the right side wears a coat very similar to Aaron’s coat.(Islamic Art and Architecture Collection)

Some iconographic elements in fact, offer an hint about the form of religiosity in this synagogue. In Wing Panel III, the figure in a chiton (identified by Kraeling as Ezra and by Fine 7 as Moses) holds an open scroll in his hand which could be a reference to the Torah scroll. The chiton has ritual fringes (Tzitzith) visible at two corners.

Another figure, Moses in the Exodus panel (WA 3) wears a chiton with fringes. Furthermore, a language similar to an Aramaic paraphrase of the Torah might be present in the tituli indicating Moses on the painting.8 A parchment discovered during the excavation in the fill of Wall Street, close to the synagogue, contains a fragmentary text very similar to the prayer “Blessing after the meal” (Birkath Ha Mazon) in Hebrew.

9

The ritual fringes and the parchment, among other considerations, allow Fine to conclude that Dura’s Jews were observant and they “participated with the rabbis in a kind of Jewish koinè.”10

Levine 11 by contrast, is very critical of these conclusions and refutes Kraeling’s use of “rabbinical sources” in the interpretation of the paintings, especially of those chronologically after the third century CE. He claims that the rabbinical attitude toward figural art ranged from “passive tolerance to hostile opposition,”12 thus opposing the idea of a Durene Jewish community observant of traditional laws and rules. Beside the fact that Midrashim and translations of the Jewish Bible (Targumin), oral or written, were probably available before the compilation of the rabbinical writings (Talmud), observance and respect of religious rules, as in modern day, is a local or individual expression.

13

The question of whether rabbinical sources were used or not, is not a purely rhetorical issue. Some contemporary scholars deny or minimize the use of rabbinical sources in an attempt to support their theory of the existence of non-rabbinical Jewish communities in the first centuries of the Common Era, as well the theory of a mystical non-rabbinical Judaism. The paintings of Dura-Europos are crucial as a “source” in supporting these theories. As Fine points out, programmatic ideas of some scholars brought them to minimize the importance of or ignore the liturgical parchment, which, together with the iconography, might reinforce the connection between the Jews of Dura-Europos and the rabbinical world.14

At any rate, using modern categories to comprehend the paintings is very challenging. Religiosity and observance of the law are characterized here by an iconographic language which goes far beyond Jewish rules (Halacha) or customs (Minhagim).

As seen above, an attempt to understand the religious background of the attendees of the Dura-Europos synagogue cannot ignore the strong influence of Graeco-Roman art. This is obviously in contrast with the sages’ prohibition of figural representations in order to prevent idolatry.15

Also evident is the chasm between strict observance of rabbinical instructions and the archaeological evidence of a vast range of artistic representations in Jewish catacombs and in the mosaics of synagogues in Israel and in the Middle East as well in Italy and Turkey. In the excavation reports, Kraeling (Kraeling 1956, 344-356) interprets the paintings of the Dura-Europos synagogue largely using rabbinical sources with the understanding that religious practices are variable. He maintains that “In general it would seem reasonable to suppose that Jewish communities existing in immediate contact with Graeco-Roman culture would have acquired from their surroundings a tolerant view of the question at issue, as the paintings of the Dura synagogue themselves may be thought to indicate.”16

As well summarized by Levine, modern scholars’ theories assume four main possible functions for the paintings: 1) to stimulate historical memory, 2) to highlight ritual symbols, 3) to complement instruction, 4) to instill messianic hope (Levine 2000, 566). But all of them are only an attempt to understand the paintings amidst a lack of comparative archaeological evidence. Or, perhaps, each of these interpretations was part of “the program” of the paintings.

Modern scholars have focused their efforts on the search for external sources or programs to support their interpretation, losing sight of the paintings themselves.17 For this reason, it is important to experience the paintings first-hand, ideally seeing them directly in person, due to the limitations associated with reproductions, photos and drawings. Hopefully, this will be possible in the future, despite the current civil war in Syria and the political circumstances.

- Kraeling 1956, 102-103. ↩

- J. Elsner, “Viewing and Resistance: Art and Religion in Dura Europos,” in Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text, ed. J. Elsner (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007), 281. T.Rajak, “The Dura-Europos Synagogue: Image of a Competitive Community” in Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity, eds. Lisa R. Brody and Gail L. Hoffman (Chestnut Hill, Mass: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2011), 142. ↩

- T. Rajak, ” Dura-Europos Synagogue,” in Brody and Hoffman, Crossroads,151. ↩

- Pamela Berger, “The Temple/Tabernacles in the Dura-Europos Synagogue Paintings” in Dura-Europos: Crossroads of Antiquity, eds. Lisa R. Brody and Gail L. Hoffman (Chestnut Hill, Mass: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2011),136. ↩

- P. Berger, ”The Temple”, in Brody and Hoffman, Crossroads,137. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 144 views this as a mourning custom of the Jews in Mesopotamia. The actual Jewish custom is to walk with bare feet and rip a portion of the dress. ↩

- Fine 2005, 179. ↩

- Fine 2005,180. ↩

- Text in: Fine 2005, 175 and in: Krealing 1956, 259. ↩

- Fine 2005, 183. ↩

- Levine 2000, 567. ↩

- Ibid. 456-458. ↩

- See: Kraeling 1956, 354. He summarizes: “This particular cycle as it is known to us at Dura moves within a definable orbit of the Haggadic tradition, that this orbit has Palestinian-Babylonian rather than Egyptian relations, that while not a few of the Haggadic details incorporated in the paintings may have been available for use at a much earlier time, the aggregate belongs to the time and place of execution of the paintings.” ↩

- Fine 2005, 43: “These scholar-rabbis (S. Cohen, L. I. Levine, J. Neusner) reflect the spirit of their day, their work paralleling a distancing of the Conservative Jewish community from traditional models of authority.” See also 174-177. ↩

- See: Mekhilta of R. Ishmael, Yitro, 6. In: Levine 2000, 452. This text lists all the cases of prohibited representations. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 345. ↩

- Wharton criticizes the priority accorded to the literary text in attributing meaning to the synagogue paintings. And moreover it is overly true that: “treating images as illustrations whose completion requires the restoration of a lost text leads to serious epistemological problems.” Wharton 1995, 39 and 42. ↩