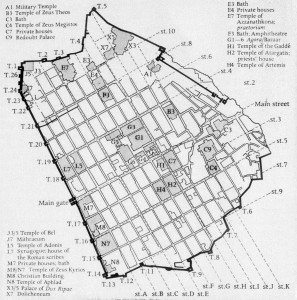

Regarding the presence of Jews in Dura-Europos, the geographical context casts light on the origin of their settlement there. In fact, since 597 BCE, the year of the deportation of the Jews to Babylon after the destruction of the First Temple, Jews settled in Mesopotamia and in a series of towns along the canal from Babylon to Nippur. At any rate, intensive contacts were held throughout the centuries between the Palestinian and Babylonian communities. Another emigration wave was probably caused by the persecution and repression of Hadrian (135 CE). The Talmud was in part a creation of the flourishing Babylonian Jewish community of the “post-exile” period. The famous Talmudic academies of Sura and Nehardea (II century CE) arose in Mesopotamia. In 258 CE, a Talmudic school was opened in Pumbemditha. (See map in “Home” for overview). Although it not possible to know the exact date of Jewish settlement in Dura-Europos, the excavation report of the Synagogue offers substantial information about the beginning of the Jewish presence in the town.

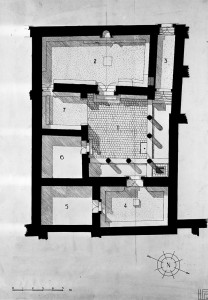

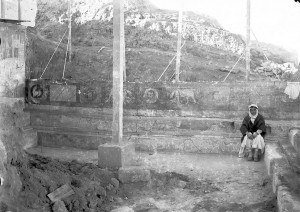

According to Kraeling,1 the Synagogue was part of a group of buildings along the wall street built in the late first or early second century CE (50-150 CE). Dura-Europos was under Parthian domination at this time, a time of growth and prosperity. The excavation report suggests that a private house was probably adapted into a Jewish house of worship early in the period of Roman domination between 165-200 CE. The location of the early building was problematic, since the proximity to the city wall blocked the cooling action of the desert’s wind and because winter rains mixed with debris and sand caused the plaster walls to become saturated.

The building had four other rooms and an interior courtyard with colonnaded porticoes. Kraeling 2 calculated that the main room (“Room 2”) could accommodate 41 persons, and the next smaller room 17. From these elements and the size of the chambers, it can be inferred that the community was modest in number and not wealthy.

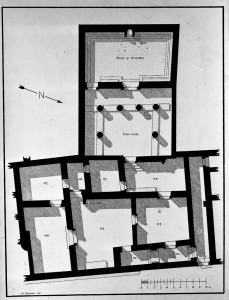

Starting from the years 244-245 CE according to the commemorative inscriptions (on ceiling tiles A, B, C ; Inscriptions 1a, 1b, 1c Torrey in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 84, Syr 85. See “Inscriptions“), the Synagogue was completely renovated, a new building was erected and many houses on the same block were probably bought by Jewish owners. This assumption rests on the fact that the houses close to the Synagogue were connected through passageways and doorways, a condition required for the observance of the Sabbath. Thus, since the complex was considered one private domain, Jews were allowed to carry objects on the Sabbath in this enclosed area. The roof of the House of Assembly was decorated with ornate and painted tiles in these years.

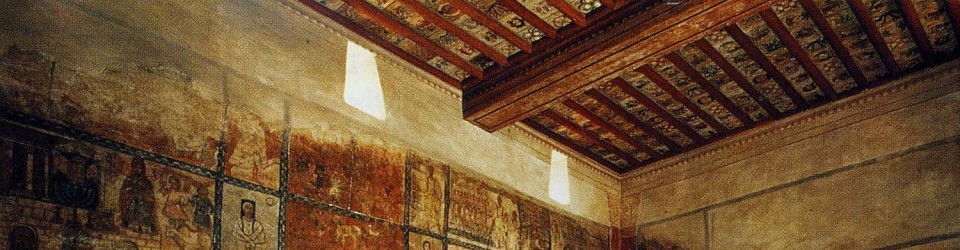

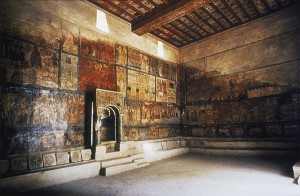

Reconstruction of the late synagogue building in the National Museum of Damascus. View of the western wall with Torah shrine and of the northern wall. Benches are visible along the walls on the bottom, where ceiling tiles were placed. (Univ. California,San Diego)

During this time, Jews had probably improved their living conditions due to trade with the other cities in northern Mesopotamia and in Palestine. Furthermore, general changes in Roman policies were more favorable to them. In 212 CE, Caracalla in fact, established the new Constitutio Antoniniana, which granted Roman citizenship to most inhabitants of the empire and abolished harsh restrictions to which the Jews were subject. Dura Europos had a vital function for the Romans as an outpost on the Parthian and, later in the third century, Persian frontier, as mentioned above. It is an outdated conceptions to consider Dura-Europos a peripheral town at “the fringe” of the Roman Empire and the significance of its geographical position for military and commercial reasons has been sharply reassessed.

The large quantity of inscriptions in three languages, Greek, Aramaic and Iranian, provide a wealth of information about the people of the community. (See the section “Inscriptions”). There was a head of the community, Samuel the son of Jeda’ya, of a priestly family (in Aramaic: Inscription 1a Torrey in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 84; in Greek: Inscription no.23 Welles in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 86), and other persons with different functions: a scribe and a treasurer. A proselyte is also mentioned, whose name is not clear, as are several people involved in the building’s construction. The enlarged room could now host “at least 65 persons”3 and the presence of Greek inscriptions might indicate that more Hellenized elements had joined the community.

This wealth was probably due to the resumption of the Roman-Persian wars and the consequent services offered by the town to the garrison.The excavation report states that three major projects were realized in the Synagogue during the years 244-256 CE. 4 1 The floor level of the House of Assembly was raised in order to install two ascending rows of benches to increase the seating capacity. 2 Wall paintings were executed. 3 Middle Persian inscriptions (dipinti) were superimposed in very visible portions of the paintings. These facts convey an image of a large and wealthy community and also reveal information about the community’s level of religious knowledge and practices and the influence of many non-Jewish cults in the town. Some scholars define Dura-Europos as a “strongly competitive religious environment 5, while others introduce the idea of “resistance” on the part of the local population to the dominant Roman influence.6

Concerning the Middle Persian inscriptions, it is still unclear why they were written directly on the painting and what they mean. (See the brief discussion in this regard in the section “Inscriptions.”) Perhaps they indicate a Persian presence in the town before the final attack. Sadly in fact, just a few years after the paintings of the House of Assembly were completed, the Persians attacked and conquered the town, defeating the Roman garrison. The great embankment built as a defense preserved the synagogue and other buildings along the wall. When the complex was excavated, the Torah shrine and its scrolls, the canopy over the aedicule, the wooden bimah, the lamp stand (whose holes are in the floor) were not found in the House of Assembly/Synagogue, nor were any mats, carpets or benches. It is not possible to know what the destiny of the population was. Dura-Europos became a deserted city, submerged by sand until its casual discovery last century around 1920 by British soldiers digging the city circuit wall for a machine gun emplacement.7

- Kraeling 1956, 327. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 328, n.36. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 334. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 335. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Elsner 2007, 285-286. ↩

- C. Hopkins, “The Excavation of the Dura Synagogue Paintings”, in The Dura-Europos Synagogue: A Re-evaluation (1932–1992), ed. J. Gutmann (Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1992), 12. ↩