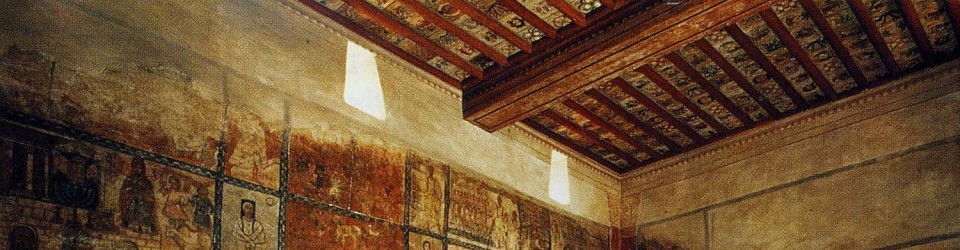

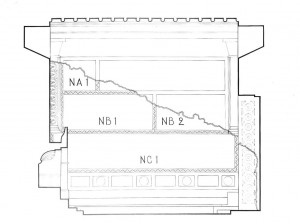

Although the Ezekiel panel was located less prominently on the northern wall (NC 1), on the right side when entering the synagogue, it highlights important motifs that also recur in other paintings and conveys an image of the Jews of Dura which helps to define their identity. For this reason, the panel will be analyzed below. After identifying some peculiar traits of the synagogue’s iconography, a brief discussion will focus on the interpretative challenges posed by the paintings in the section “Iconographic Elements and Jewish Identity.” The Ezekiel panel was located in the lowest of the three registers close to the worshippers, a fact which counterbalances its position on the side. The narrative is displayed with vivid intensity and was probably well known to the Jews in Dura. Ezekiel, in fact, a prophet of the Exile, lived in 593 BCE in the Babylonian area, i.e. a geographical, cultural and religious environment not far from Dura-Europos. (See “Home“).

The narrative of the paintings refers to the Book of Ezekiel. The prophet writes about his visions inspired by God with pain and bitterness for Israel’s past sins, which caused the destruction of Jerusalem’s Temple and the exile. He prophesizes a messianic time in which the dead will be resurrected, Jews will live united in the land of Israel (the tribes of Joseph and Yehuda), the Diaspora will end and King David (Messiah) will reign over them “forever.” In order to represent these concepts in an intuitively understandable iconography, the artist(s) developed dramatic narrative sequences multiplying the figures to illustrate the action and expressing abstract concepts through images of various stages of life/after-life: the men, the dead, the winged creatures (souls or angels). The sequence (A-C) can be read from left to right. It is also possible to read it from C to A, according to others interpretations. Since Section C does not seem to directly form part of Scenes A and B, it will not be considered here. 1

In general, the drawings are considered frontal. In Hachlili’s judgment (Hachlili 1998, 136), they are based on stereotypes and lack individuality or realism. Kraeling notes the absence of proportion in the size of the medium figure in Section A and the dimensions of the male corpses at the base of the mountain (Kraeling 1956, 183). For example, the hands laying on the ground are two-dimensional.

In Section A, an identical male figure with brown curly hair and a narrow mustache (a frequent iconography for men in the paintings) appears three times in different positions and gestures, representing the prophet Ezekiel. The figure wears a long-sleeved Persian tunic with vertical stripes in the front and a white belt, trousers (the so-called “tailored suit”) and soft boots. In the first part of the sequence, the figure on the left is grasped on his head by the fingers of the Hand of God coming from above, while his own arms are outstretched in a “floating” position. In the second part of the sequence, the figure is pointing with his left arm upwards; the other hand, palm wide open, is indicating the dismembered parts of bodies on the floor; over his head is The Hand of God, palm outward. The third figure in the sequence is extending his right arm upward to the (third) Hand of God, while his left arm is pointing to the mountain at his side. Kraeling clarifies that: “The open Hand of God denotes the communication of a divine revelation, the upward reach of the human hand its receipt, and the outward reach of the other human hand its transmission” (Kraeling 1956, 188-189).

The identification of the figures in this painting is based on the passage in the Book of Ezekiel, where the expression “God’s hand” recurs frequently when God is communicating with him and after he starts to prophesize.

The first figure on the left seems literally carried by the hand above in the picture as in Ez. 37, 1: “The hand of the Lord was upon me and carried out in the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the midst of the valley, which was full of bones.”

2

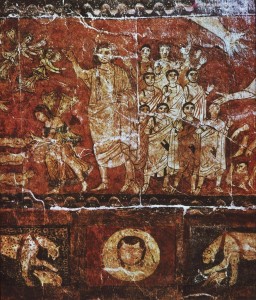

Ezekiel panel, Section B (Yale Univ. Art Gallery)

In the continuation of the painting, referred to as “Section B,” Ezekiel, the figure wearing the tailored suit very similar to the others, stretches his right arm slightly upwards towards The Hand of God and his left arm to the floor. Three dead bodies lie on the ground to both sides of him. The dead and their parts in the bottom of Sections A and B represent Israel 3 In fact, in the center there is a mountain with a deep cleft from which dismembered bodies are coming out. They are later reunited, and then lie on the ground. There are no bones in the pictures as Ezekiel’s text would suggest, but body parts (feet, arms/hands and heads).On the ground a winged figure holds the dead man’s head and revives him, while three other small winged figures fly towards the three corpses on the ground. The passages Ez. 37, 9: “Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live” and Ez.37, 10: “Breath came into them” help to clarify the picture.

The first, more elaborated figure is, in fact, “Breath” in the shape of a winged creature similar to a type of Nike; the three little winged figures, similar to a type of Psyche, seem like souls entering the corpses.

It is noteworthy that the word breath, “ruach,” in Hebrew is feminine. Since the artist lacked any model for “ruach,” he drew a Greek prototype of Psyche according to the “type of Psyche that was particularly beloved in the east and that appears commonly on Syrian sarcophagi.”4

This is a significant instance of an iconographic transformation of a pagan symbol.

The sequence continues with two male figures in chiton, himation and sandals. The first stretches his hand in a gesture with extended thumb, index and middle fingers, while his last two fingers are folded up. He is indicating the returning souls and the whole resurrection scene. This gesture, which is a forerunner of the sign that later became the symbol of the benediction in Byzantine iconography, here is a sign of address.5

In the middle of the two men in chiton, a group of ten men dressed in the same way is drawn on a smaller scale. The second man in chiton is identical to the first with the exception of his arm, which points to the group in the middle in a ostensive way, above his head the (fifth) Hand of God.

In this scene the two men in chiton represents Ezekiel assisting the final act of the resurrection. After God brought Ezekiel into the Valley of the Dry Bones, he opened the earth. From the depth of mountain’s cleft, dismembered dead have come into the world in order to be reunited and resurrected. This means the end of the exile with a reconstituted Israel, represented by the group of the ten men in chiton between the two “Ezekiels.” The identity of the two larger size men is very debated; one major difficulty is the different dresses worn by the principle “actor,” the prophet Ezekiel.

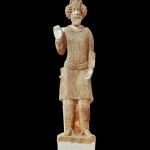

An example of “tailored suit”. Statue of the Parthian king Sanatruq I. Hatra. Second c. CE (Scala Archives, Florence/ Art Resourse, NY)

The change of dress might indicate a double function of Ezekiel as priest in Persian garb, and as “prince of his people” in Greek attire. 6 In the Synagogue’s paintings, the Persian tailored suit was typical for court and temple personnel while the Greek chiton and himation were typical for prophets.7

The Ezekiel panel highlights these interesting motifs, which are also typical of other paintings in the synagogue and have here a strong visual impact:

-The representation of The Hand of God as an expression of God who resurrects and accomplishes wonders.

-The use of dresses (Greek, Roman and Persian attire) to indentify the figures.

-The relevance for the worshippers of the idea of Jewish identity as the exiled “nation” expressed by the prophet.

-The messianic belief of resurrection, according to the text of Ezekiel, regarding all Israel.8

– Graeco-Roman models as in pictures of the “Ruach,” in the Psyches, in the men in chiton, are used for abstract Jewish concepts.

- The continuation of the painting in Panel C is considered by Rachel Wischnitzer part of the narrative of the eastern wall (EC 1) and thus connected with the story of King David. It is interpreted as “Joab’s punishment” (Wischnitzer 1948, 36-37 and 42-43). According to Wischnitzer, the man in a chiton in Panel B is Ezekiel, but the other figure between the dead corpses is King David, from whom the sages said Mashiach (Messiah) will descend. A convincing solution is still to be found. ↩

- All translations are from: Koren Publishers Jerusalem. The Holy Scripture. The English text revised and edited by H. Fish. (Jerusalem: Koren Publishers Jerusalem LTD, 1992). ↩

- As in Ez. 37, 11: “These bones are the whole house of Israel.” ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 184-189. He underscores a relation of the bigger winged figure,”Breath”, with the Nike of Paionius and identifies the three winged figures as the four winds mentioned by Ezekiel. ↩

- Kraeling 1956,194 ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 184-189. ↩

- The tailored suit was of Parthian origin but also to be found generally in the Orient: “Rulers, both cosmical and temporal, and the draped robe were united.” B. Goldman, “The Dura-Europos Costume and Parthian Art,” in The Dura-Europos Synagogue: A Re-evaluation (1932–1992), ed. J. Gutmann (Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1992), 61-64. ↩

- For this concept see: Wischnitzer 1948, 42 ↩

Whoever the author of this post is, I do not believe that the paintings are in the Jerusalem. Who transported them from Damascus?

Pingback: Destroyed By Isis, This Ancient Syrian Synagogue Had Jaw-Dropping Murals | Jewniverse