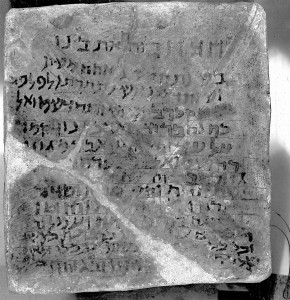

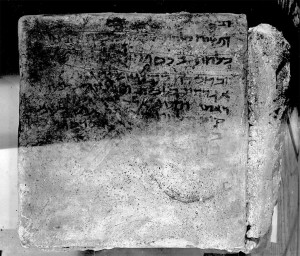

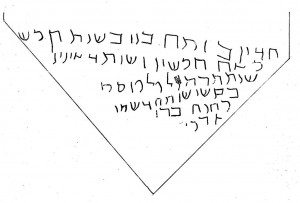

The most important inscription is the dedication in Aramaic of the later synagogue building on three ceiling tiles, Tiles A, B and C, found in the synagogue embankment, as mentioned above. Tile A was broken in three pieces and later joined together; the cracks are visible in the photo. Since reading the tiles is very challenging, Torrey also used infrared photos. The text is painted in black in Tiles A and B. In Tile C, the text is first scrawled and then painted in black in a lower portion of the tile. There is agreement that Tile B with its eight lines is the continuation of the text in Tile A, although J. Oberman1 considered Tile B a separate liturgical text. Tile C was discovered through a fortunate accident. In fact, this tile was painted with a floral decoration that flaked off during transportation revealing the graffito and the painted copy of the beginning of the text in Tile A.

Inscription no. 1a Torrey in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 84.

Translation in English (by Torrey in Kraeling 1956, 263-264).

Note: In Kraeling’s edition, the English text tries to reproduce the full size of the lacunae in the Aramaic inscription in order to make the missing parts in the lines visible. In the text below, there is only a generic indication of lacuna (…) without any indication of the quantity of the missing letters or sentences, which would be impossible in an English text! As is customary, brackets [ ] are used to integrate a lacuna. Since the end of the inscription is very damaged, the sentences are incomplete and Torrey offers only possible translations of isolated words. Words in parenthesis ( ) were not in the text, but were added by Torrey.

The Hebrew transliteration follows the translators. For example: Yeda’ya in Torrey is Yedaya in Noy-Bloedhorn. The name “Abram” is left this way and not written as usual as Abraham, since it is translated in this fashion from the Aramaic by Torrey and since the Greek inscription was written without the Hebrew “heh.”

(Tile A)“This house was built in the year 556, this corresponding to the second year of Philip Julius Caesar; in the eldership of the priest Samuel son of Yeda’ya, the Archon. Now those who stood in charge of this work were: Abram the Treasurer, and Samuel son of Sapharah, and (…) the proselyte. With a willing spirit they [began to build] in this fifty-sixth year; and they sent (…) and they made haste (…) and they labored in (…) a blessing from the elders and from all the children of (…) they labored and toiled (…)Peace to them, and to their wives and children all. (Tile B) And like all those who labored [were their brethren…], all of them, who with their money (…) and in the eager desire of their souls (…) Their reward, all whatever (…) that the world which is to come (…) assured to them (…) on every Sabbath (…) spreading out [their hands] in it (in prayer).”

In Tile C, the graffito precedes the dipinto placed in the center. A scheme made by Obermann clarifies the location of the inscriptions.2 With some significant variations, the graffito repeats lines 1-5 of the text in Tile A until the word “archon”; the dipinto repeats lines 1-7 and is suddenly interrupted. The tiles are today in the Yale University Art Gallery. These inscriptions were probably exercises or drafts and today are instrumental as tools to help decipher the texts.

Inscriptions nos.1b and 1c Torrey in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 85

This dedicatory inscription gives a face to some of the unknown people who built, decorated and attended the synagogue. The renovation of the synagogue started in the year 556 of the Seleucid Era, which corresponds to 244 or 245 CE.3 The text also mentions the Roman year: the “Second of Philip [blank] Kaiser,” where Torrey fills in the blank with “Julius.” The blank and the omission of the word “Julius” is interpreted by some scholars as a case of damnatio memoriae. Kraeling believed it to be an erasure since other cases of erasure concerning Philip were known and because of the hostility to Philip in Mesopotamia.4 If this is true, it would have been a strange damnatio, since the words Philip and Kaiser were left there. According to other theories, the incomplete erasure was an error by the person in charge of it5 and/or other natural causes might have damaged the tile.

Philip reigned for only three years, and, according to Millar, he replaced Gordianus III in 244 after the latter was killed during his campaign against Shapur. Philip’s short reign was thus very relevant for Dura-Europos, since it marked the beginning of a decade of “Romanization,” when Dura probably gained the status of colonia.6 In this context, the mention of the emperor might express the need of the Jews to be on good terms with the Roman forces. In fact, the Jews had solid relations, established in ancient times, with the Persians, whom the Romans were fighting in continuous campaigns in this period.

Line 9 makes another obscure chronological reference: “With a willing spirit they [began to build] in this fifty-sixth year.” The number fifty-six, which recalls the number “556” of the Seleucid Era, might form part of the internal chronology of Dura’s Jewish “community.” The suggestion that this reflects a Jewish chronology of the “destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem” (70 CE) has to be rejected since it would result in the year 125/6 CE circa (70+56), which does not match the year 556 of the Seleucid Era. Unfortunately, there is no clear answer to this question.

Another chronological reference is mentioned after the Roman chronology: “In the eldership of the priest Samuel son of Yeda’ya, the Archon.” Eldership is in Aramaic קשיש (kashish) and the function is translated in Greek with the word presbyteros, in Hebrew with זקן (Zaken). The fact that Samuel was a priest (כהנה = cahana) does not imply a priori that he had any political responsibilities in the community. Furthermore, there is disagreement among scholars about who was the archon, Samuel or his father Yeda’ya.7 Samuel was the archon according to Torrey’s translation but, for Noy-Bloedhorn, the archon was more likely the father Yeda’ya.

The archon’s function as a leader might refer to the Jewish community at large or to the synagogue. The word archon often appears together with the word “archisynagogue” in inscriptions and texts of the first centuries CE within a wide geographical area. “Archisynagogue” could be translated with the Hebrew word Rosh Knesset, ראש כנסת, Head of the congregation. In Acmonia, in Asia Minor, for example, the archon with two archisynagogues undertook the restoration of the building.8 These offices were held by a single person or by two persons, with many geographical variations. At any rate, as Levine (Levine 2000, 402) notes, in small communities there was little distinction between the organizational framework of a community and that of a synagogue. The historical background and geographical context do not provide much help in the identifying the archon in the inscription.

New insight might possibly be found in a short Greek inscription in the synagogue, among the three remaining building inscriptions in Greek. In this inscription, Samuel is called πρεσβύτερος, presbuteros, elder.

Inscription no. 23 Welles in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 86. Now in National Museum in Damascus.

Σαμουὴλ

Εἰδδέου

πρεσβύτερος

τῶν Ἰουδέ-

ων ἔκτισεν.

Transliteration: Samuel Eiddeou presbyteros ton Iudeon ektisen.

Translation of Noy-Bloedhorn, ( IJO 2004, 149):

“Samuel,(son) of Yedaya, elder of the Jews, founded (the building).”

According to the Talmud, presbuteroi had the honor to sit in the synagogue in Alexandria (first century CE). 9 Their leadership function was to sit on a board from which archontes were selected. The question arises here why the Greek inscription does not mention the Greek form “archon,” which is used in the Aramaic text, and calls Samuel presbyteros instead. One possible answer is that the father Yeda’ya was the archon and Samuel had the function as an “Elder” of the Jews, a reference to the “community” not only to the synagogue. Kraeling suggests that Samuel alone held the highest authority in the community, namely the קשיש (kashish) or presbyteros. However, he believes that Samuel was also an archon, a function shared with other people on a board which administered the affairs of the community and of which he was chairman.10

Together with others, Samuel was in charge of the renovation and probably of the funding for this major project. In the Aramaic inscription, Abram (Abraham in current transliteration) the Treasurer, Samuel son of Saphara, and a proselyte were in charge of the work. These names are also confirmed in the other two remaining Greek inscriptions.

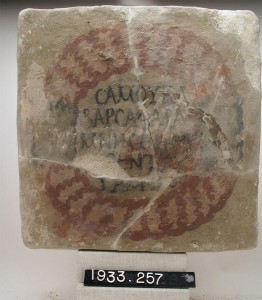

Inscription no. 24 Welles in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 87. Now in the Yale University Art Gallery.

Σαμουὴλ

Βαρσαφάρα

μνησθῇ ἔκ-

[τ]ισεν ταῦ-

τα οὕτως.

Transliteration: Samuel Barsaphara mnesthe ektisen tauta outos.

Translation of Welles ( Kraeling 1956, 277): “Samuel, son of Sapharas: may he be remembered! He built this (building) thus (as you see).”

Translation of Noy-Bloedhorn, ( IJO 2004, 150):”Samuel son of Saphara [Barsaphara], may he be remembered, founded these things thus.”

In both inscriptions above (Syr 86-87), Samuel Bar Yeda’ya and Samuel Bar Saphara “build,” ἔκτισεν, the synagogue or “these things,” as in the translation of Noy-Bloedhorn. They had a major role in the renovation, because, as already pointed out in the “History” section, the synagogue complex was not rebuilt from the foundation.

The third inscription mentions Abram (Abraham), Silas and Salmanes, who probably helped with financial contributions. The name Arsaces in the inscription is unclear.

Inscription no. 25 Welles in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 88. Now in the National Museum of Damascus.

Ἄβραμ

καὶ Ἀρσά-

χου καὶ Σιλᾶς

κὲ Σαλμάνης

ἐβοήθησαν.

Transliteration: Abram kai Arsachou kai Silas ke Salmanes eboethesan.

Translation of Noy-Bloedhorn, ( IJO 2004, 152): “Abraham and Arsaces (?) and Silas and Salmanes helped.”

Abram is the treasurer mentioned in the Aramaic inscription. Silas and Salmanes are unknown. Since Arsaces is in genitive, the text has been the subject of much conjecture. Here, it suffices to say that it is not clear if “Arsachou” is a patronymic of Abram or a mistake of the writer.11 The name Arsaces is Persian. Salmanes is a very common variant of Salomon in the North-Semitic area.

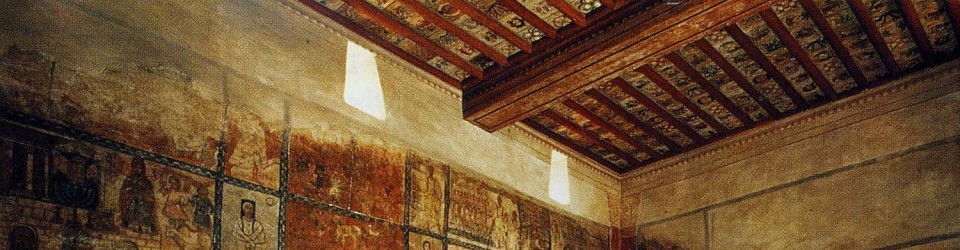

After this brief survey, a final question arises: why were such important dedications on ceiling tiles, where synagogue attendees could scarcely see them. Stern suggests that the “donors were interested more in divine than human recognition for their deeds.”12 Noy-Bloedhorn assumes that there was no more suitable space left on the walls.13 Both answers are unsatisfactory. If the donors were not interested in human recognition, they would not have commissioned the inscriptions at all but would have remained anonymous, as often happens today. Regarding the lack of space on the synagogue walls completely decorated with the paintings, it would not have been difficult to plan an appropriate space for a building dedication before beginning the work, as is usual in such cases. The reason for this decision is probably to be found in the peculiar local custom of placing dedications and decorations on ceiling tiles as in the “House of the Roman Scribe,” where there were 12 portraits with inscriptions on tiles and as in “Tower 15,” where one was found 14

- See: Torrey in Kraeling 1956, 262. ↩

- Seen in: Torrey in Kraeling 1956, 267. ↩

- The uncertainty is due to the fact that the date of the beginning of the Seleucid Era changed in each town. See: IJO 2004, 144. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 338. ↩

- IJO 2004, 144. ↩

- Millar 1994, 154-155. ↩

- Levine 2000, 126 assumes that Samuel was the archon. ↩

- Seen in: Levine 2000, 400. The information is in: B. Lifshitz, “Donateurs et Fondateurs dans les Synagogues Juives: Répertoire des Dédicaces Greques Relatives à la Construction et à la Réfection des Synagogues,” Cahiers de la Revue Biblique 7 (Paris : Gabalda, 1967), No. 33. ↩

- See Talmud, Tractate Sukka 4:6. According to Levine, the terms archon and presbyteros, which are common in diaspora inscriptions, do not appear in Palestinian inscriptions written in Hebrew or Aramaic. Levine 2000, 407 and 422- 424. ↩

- Kraeling 1956, 331. ↩

- Welles in Kraeling 1956, 278. ↩

- Stern 2010, 501. ↩

- IJO 2004, 142. ↩

- These data are in Stern 2010, 485. ↩