In its beginning, the synagogue of Dura-Europos was a very sober place with none of the splendid decorations that made it so famous worldwide through the centuries. The excavation report offers interesting details about the synagogue building prior the great renovation of the years 244/245 CE.

The decoration of the early synagogue was conventional and plain, characterized by geometric forms and color schemes.

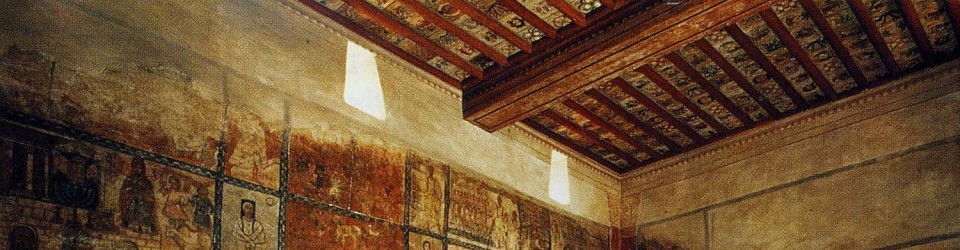

The ceiling was painted in imitation of a coffered ceiling with bright colors, including red and blue. With the renovation of the structure of the building, the decoration of the walls in the House of Assembly changed as well. The walls were painted from the ceiling to the dado with beautiful, colored paintings located on three structural elements: ceiling, walls and Torah shrine.

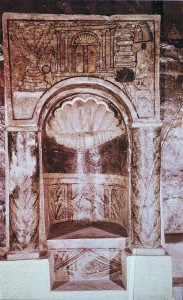

Torah shrine with the paintings; first stage decorations of the earlier building (Univ. of California, San Diego)

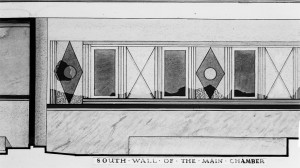

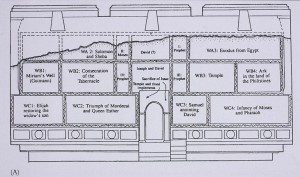

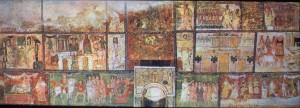

The walls were about seven meters high. Based on current knowledge, such a large variety of paintings cannot be found in other surviving synagogues of the same or later periods. The quantity of paintings remaining, 60% of the total, “exceeded that of any comparable structure in the entire city” (Kraeling 1956, 39), such as the Mithraeum, the Christian building and the Temple of Bel. Kraeling subdivides the wall paintings into five zones, starting from the uppermost zone, the so-called “first register,” which is lost, up to the dado. A second zone (Register A), third and fourth zones (Registers B and C) follow. The fifth zone was the dado close to the benches with imitation marble and representations of animals and masks.

The embankment built by the Romans preserved most of the paintings but not the highest portion of the wall, causing the loss of the decorations. This happened to the most of the southern and eastern walls, where only some paintings from the lower register are left and to the upper part of the northern wall. The western wall was oriented towards Jerusalem and hosted the Torah shrine. It is the best preserved wall. This text uses Kraeling’s classification according the diagrams of the excavation report: W=West wall, Registers A, B, C; N=Northern wall, Registers A, B, C, etc. Paintings close to the Torah shrine in the western wall are called “wing panels.” Contrary to the frequent mention of “frescoes,” Clark importantly notes that: “The paintings at Dura are not frescoes with the colors embedded in the plaster but made in tempera and so easily blurred if incautiously rubbed.”1 As a consequence, they faded quickly when they were exposed to the light after their discovery.

The surviving paintings represent some of the most important stories from the Jewish Bible, including special translations, Midrashic and Haggadic materials. The quantity of writings and publications about the paintings is large and there is barely a topic that has not been discussed. The western wall’s paintings have been studied profusely because of their prominent position on the wall where the Torah shrine was located and also because they were in front of the main entrance and were the first seen by visitors. To modern viewers, they offer the advantage of being well preserved.

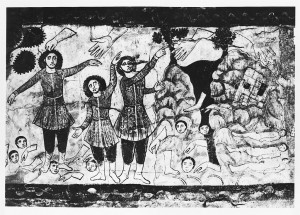

While on the southern and the eastern walls only parts of the lower registers are left, on the northern wall a complex painting was preserved, identified by Kraeling as “Ezekiel, the Destruction and Restoration of National Life” and by Wischnitzer as “Ezekiel’s Vision of the Resurrection of the Dry Bones.”2