The name “Dura” stems from an ancient Akkadic word “Duru,” which means wall and thus “fortress.” The area of Dura was populated as far back as the Assyrian Period. Sherds of new Assyrian language (New Assyrian Period: circa 1000-612 BCE) in fact were found at this location, which was situated on an important ancient route connecting Syria with Babylon.

In about 290 BCE, King Seleucus I Nicator, one of the successors of Alexander the Great, founded on the site of ancient Dura “Europos,” which was referred to by ancient sources as the “foundation of the Macedonians.”1 This is because the name “Europos” might refer to a town in Macedonia, which was the birth place of the king, or to a town on the Epirothe-Thessalian frontier. Dura-Europos was a military garrison for the defense of the Eastern border and land was allotted to its members. At the beginning of the first century BCE after many unsuccessful wars and the death of the Greek-Hellenistic kings (Demetrius II and Antiochus III), Dura-Europos fell under Parthian rule.

As a military garrison, Dura-Europos and its inhabitants offered services and supplies to the armies, thus acquiring a certain degree of wealth. The Parthian Period represented a relatively prosperous and peaceful time for the town. Its geographic location close to major towns in the east (e.g. Palmyra, Hatra, Babylon) made it an important center for traders and travelers. After the Roman Emperor Lucius Verus waged war against the Parthians (161-166 CE) and a victorious battle at Dura Europos, the town fell under Roman rule. Nonetheless, the ensuing years were marked by constant tension with the Parthians on the Eastern border. In the 220s, the Parthian Empire was overthrown by the emerging Persian dynasty, which did not hide its ambition to regain the territories of the ancient Persian Empire.2 In 231 CE, the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander had some success in regaining Hatra and other lost territories. But this lasted only for a short time because Severus Alexander was killed in 235 CE and the Persians came to Dura-Europos later in 239 CE. In 240/41 CE (or 239/240), Hatra was re-conquered by the Persians. In the year 241 or 242, Shapur became king of the Persian Empire. He recalls a campaign of the Roman Emperor Gordian III in Babylonia in 242-244 CE in the famous trilingual inscriptions with the records of his victories (Res Gestae Divi Sapori). During this war Gordian was killed and replaced by Philip, the emperor mentioned in an inscription on a tile of the Synagogue’s ceiling. According to Shapur’s inscription, Philip became a tributary to him, a fact not present in the Roman version. But since the following years were relative peaceful, a treaty was likely to have been made.

In Dura-Europos, there are many records of the Roman garrison, especially papyri and inscriptions which provide a great quantity of information about the life in Dura. Detachments of the IV and the XVI Legions built the shrine of Mithras in 209 CE. Another legion’s detachment (IV and III Cyrenaica) built an amphitheatre in 216 CE. The XX Cohort of Palmyrenes was stable from the 190s to the end of Dura between 254-256 CE.

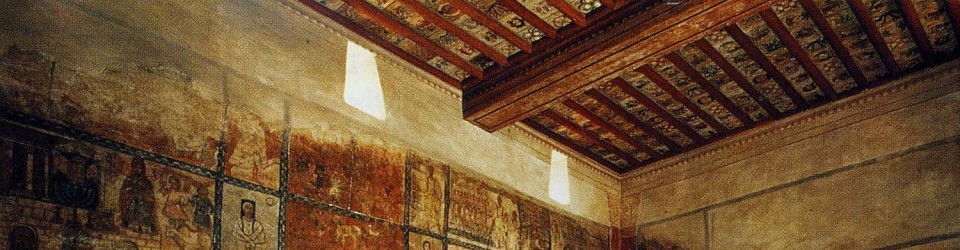

While the legatus was in northern Syria, ten tribuni were in the town. One of them, Iulius Terentius, is represented making a sacrifice to the Gods with his men in a wall painting of the Temple of Bel. An epitaph written by his wife in Greek reports that he died in battle, perhaps in the Persian attack of 239 CE.3 The Roman garrison remained in Dura until 254 CE circa. A papyrus of 254 CE, a Greek divorce deed of a soldier from the IV Legion, can be considered the last document of Roman Dura. Since the town is still defined as being autonomous in the deed, the final capture of Dura likely happened in 256 or 257 CE.4

The Persian attack on the town about 256 CE was the end of Dura-Europos, but not of its buildings, which in fact were protected precisely by the defensive embankments that the Roman soldiers had built against Shapur.

- Isidore of Charax, Parthian Stations, 1. Seen in P.L. Kosmin, “The foundation and early life of Dura-Europos” in Dura-Europos: Crossroads to Antiquity, eds. L. Brody and G. Hoffman (Chestnut Hill, Mass: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2011), 95-96. ↩

- F. Millar, The Roman Near East, 31 BC– AD 337 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 147-152. ↩

- Millar 1994, 132. ↩

- Millar 1994, 162. ↩