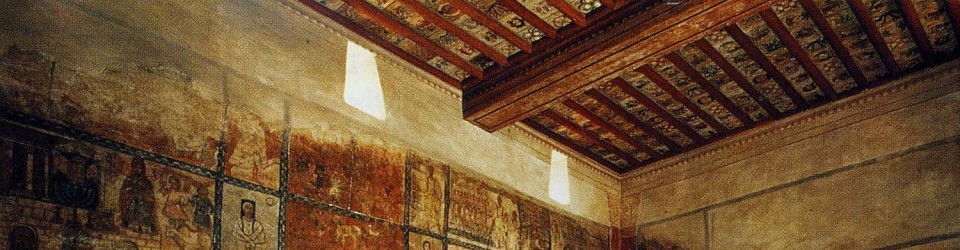

There is nothing as enigmatic as the Persian inscriptions, which, even when deciphered and translated, escape satisfactory explication and generate interminable conjecture. These inscriptions (12 dipinti and 3 graffiti) are preserved on the wall paintings in the National Museum of Damascus. The pattern of most inscriptions is as follows: On a certain date a dipivar alone or together with another person came to “this house” (=synagogue) and “this picture” was looked at by them. The inscriptions are located on Register C, at the bottom, on the Purim panel (WC 2), and on the Elijah (WC 1) and (NC1) Ezekiel panels, showing a connection with stories which took place in Persia and with the topic of resurrection. Dipivars, scribes, had typical Zoroastrian names and a Zoroastrian calendar is used in the inscriptions together with the regnal years of the Sassanian King Shapur I. (See “History” ).

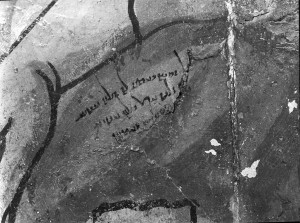

Inscription no. 44 Geiger in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 113: Translation by Noy-Bloedhorn (as in IJO 2004, 189).

(a) ” The month Mihr in [the year] 14(?) and the day Frawardin(?), when Hormezd the scribe, and Kandag, the servant and the scribe of Tahm [or valiant scribe],

and this servant of the Jews to this edifice of the God [of] the Gods of the Jews came, and this picture they beheld, and they looked and beheld [……]looked, [………… ] the picture […..]

(b) Judgment is near.

Besides the inscription indicating the visits, there is one on the Elijah panel that expresses more personal feelings. This is Inscription no. 55 Geiger in Kraeling 1956 = Syr 121. Geiger’s translation is:

“Praise to God, praise! For life, life eternally he gives (..?)”

Noy-Bloedhorn’s translation (IJO 2004, 200) is slightly different with Gods instead of God.

The widely accepted conclusion is that the officials were Persian and non-Jews. They came in the year 253 CE to Dura, which was temporary occupied by the Sassanians of King Shapur.1

According to Polotsky: “The visitors may have been members of the retinues of ambassadors sent by Shapur to Dura before and during his great invasion of the Syrian provinces of the Roman empire.” 2 In Kraeling’s view 3, the inscriptions were made in order to grant safety and immunity to Jews during a temporary occupation.

It is remarkable that these inscriptions were professionally written and incorporated neatly into the paintings by no means with any intent to damage them; to the contrary, they were respectful of the shapes and discretely placed on dresses, drapery, legs or other locations. There is no answer why so many dipivars were in the synagogue or why inscriptions were necessary to protect the Jews. A further difficulty is the fact that the content of the dipinti on the Ezekiel panel (Syr 124-125) and on the Elijah panel is completely different. These dipinti show religious feelings and do not mention dipivars.

Hopefully, new research will find an answer to some of the many still open questions.